I work in science for a living. The field of genetics and biotechnology specifically. My laboratory uses artificial intelligence daily. Need to optimize a protocol? ChatGPT can do that for you. Figure out a bug in your code? GitHub CoPilot can help. Each week a new flavor of machine learning seems to debut, each boasting its own listicle of optimized search engine attributes.

The robot revolution has only just begun and quite frankly I already feel like I am drowning. I envy younger and more educated coworkers who are better adept at taking to all these new devices and processes like fish to water. Meanwhile I am more like a cat adrift at sea trying to swim but not naturally inclined to being wet and so far from dry land.

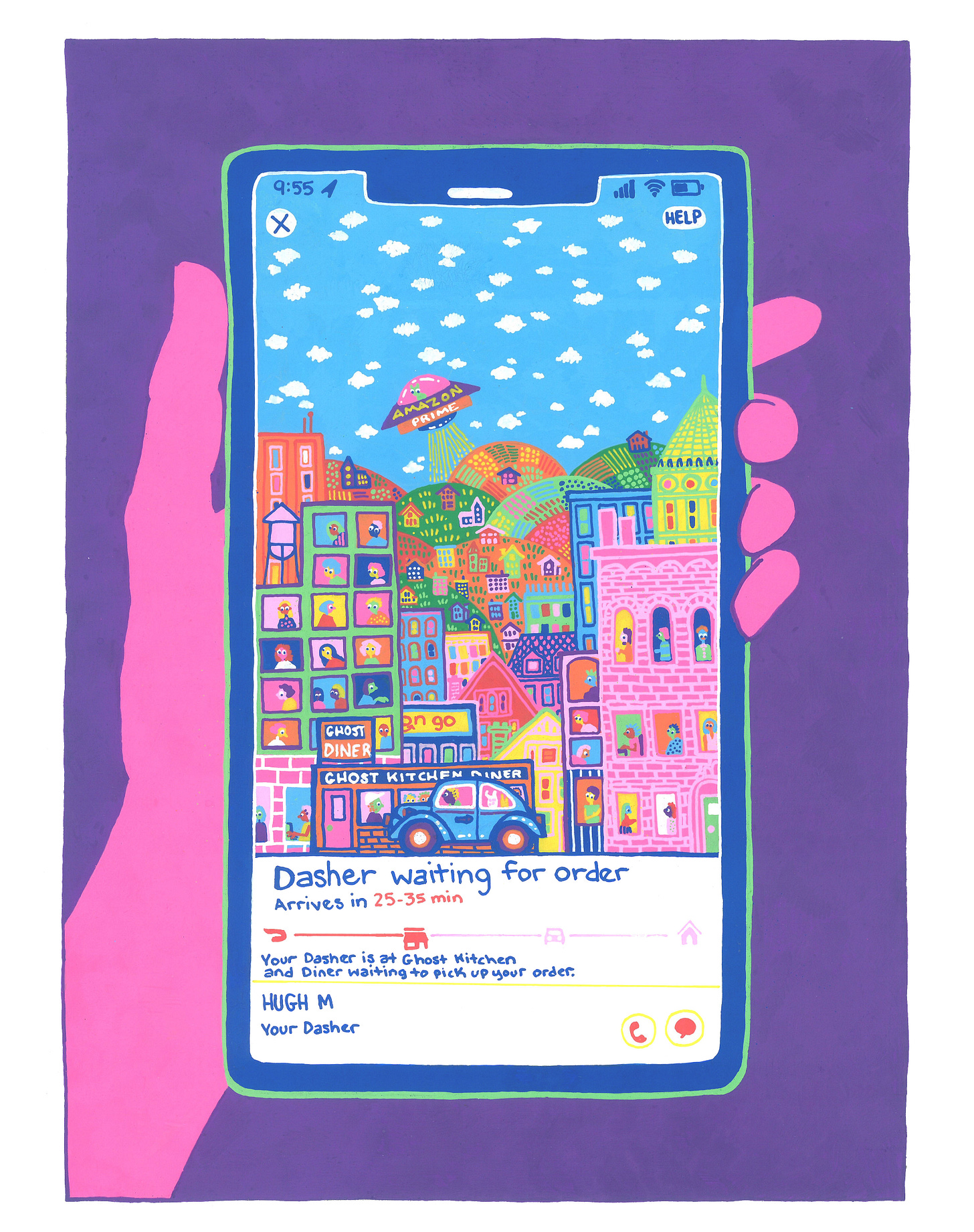

It is strange to think that it was only two years ago when AI first intersected with my life, and it was not through my day job but my side hustle. I make art as you may have deduced from the hand drawn illustrations I use to break up my writing and bring some visual interest to a wall of words. Everything I have ever illustrated has been by hand. I am immensely proud of this fact. If I cannot convey an image in analog form, I start over and try again until I can train my hands to render it correctly.

Art is pain. It is the pain of never being good enough and struggling for the unattainable dream of perfection. While this may sound frustrating and futile because it is; striving for flawless skill with each new piece inevitably does make you a better artist. Art is in fact sport regardless of what people tell you. To create original work is to be constantly competing with yourself, and you must exercise to stay in shape.

I have problems with art where a stray mark can be deleted rather than re-worked. I get angry when instead of relying on skill accrued over years of experimentation, a mistake like an awkward line or an errant blob of paint, can just be forgotten about instead of arduously fixed by hand. The true test of artistic skill is not how you avoid errors in artwork but how you maneuver around them and magically fix them without the observer knowing they were accidents in the first place. That is called “talent.” So naturally I have huge issues with AI generated art.

I remember when AI art apps started populating my Instagram feed. Lensa was the most prolific and awful of the initial robot Picasso bunch. The images it generated were vile Lisa Frankenstein-esque creations. A few weeks after the carousels of selfies fed into the machine and spat out with Marvel comic-like features became less ubiquitous on social media, it was revealed that Lensa had been using original art from unassuming artists to train its AI. In other words, it had been copying its stylistic characteristics from artists who had not given the company–Prisma, the makers behind Lensa, permission to use their work. Artists only found out about Prisma’s use of their art when it was evident through the mishmash of aesthetic qualities of its artificially generated social media viral portraits. Style is an extremely tricky thing to obscure–even for a robot.

Lensa proved that AI art was nothing but a cheap artifice for stealing instead of learning from the creative process and making something utterly unique. And ever since our tech overlords gifted us with the ability to turn our iPhone photos into Disney princess vanity portraits with chiseled cheekbones, airbrushed skin, dinner plate eyes, and ample cleavage, AI has been slowly whittling away at creativity and ingenuity across the internet.

A strange thing you learn when taking figure drawing classes is that ugliness is more interesting than beauty. Symmetry and smooth lines make for boring drawings. A weathered old face, a bulbous or withered form, make for more intricate and fascinating studies of the human body. Short tangential angular lines rather than long flowing curvilinear ones make a portrait more realistic.

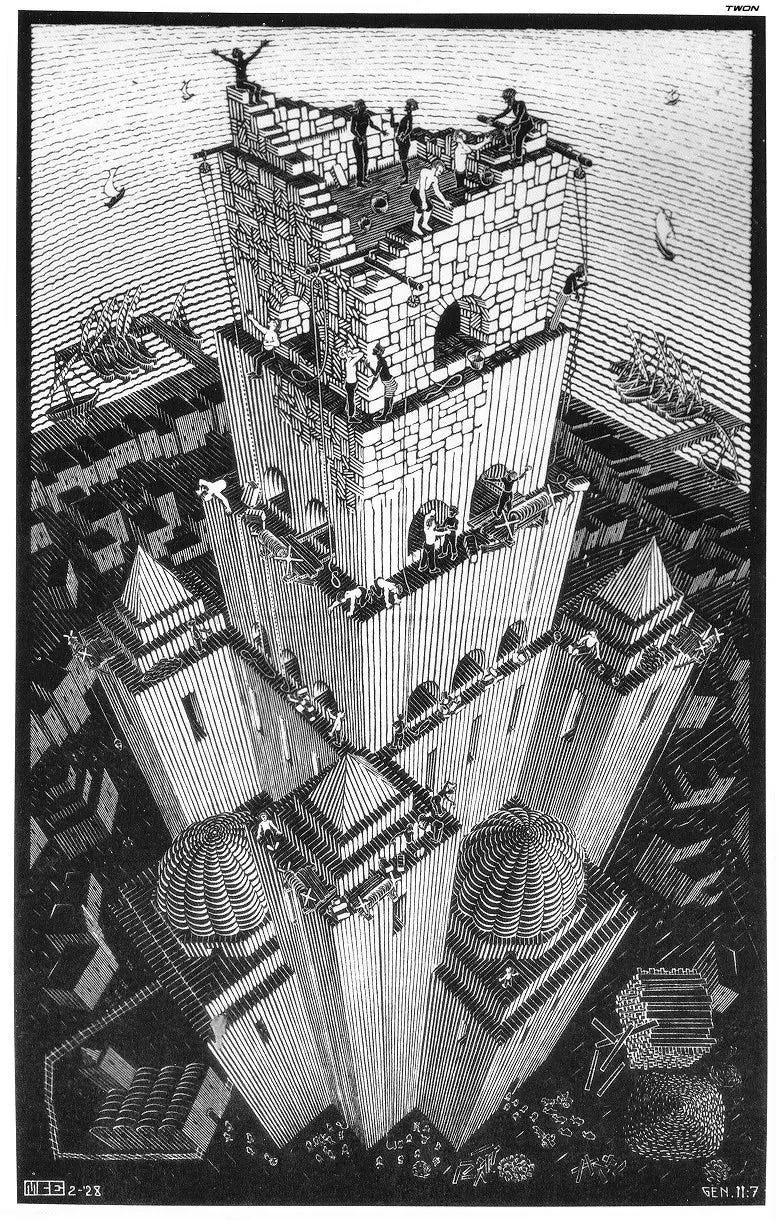

I have always been fascinated by the technique of using short sharp strokes for a more amplified realistic form partially because it draws so much knowledge from mathematics-specifically trigonometry and calculus (calculus was my favorite math subject in school). Much like the use of vanishing points and Chiaroscuro creates the illusion of dimension, mass, and volume. The best parts of art are those that play with suspension of disbelief by using concepts from our mathematical universe (anyone else an M.C. Escher fan?).

When you are trained to use the tools of the masters you can purposefully start manipulating them and bending them to your stylistic will-or ignore them all together. Being an artist in control of your craft means that you are aware these techniques are open to you and that you can command them at your own discretion. Picasso and Pollock both had the ability to perfectly render the human form. What makes their art worth studying is that they created abstractions despite their technical prowess.

I come from a city with one of the most important collections of modern art and post-modern art in the world. The Albright-Knox Art Gallery now called the Buffalo AKG Art Museum (full disclosure I did intern there many moons ago) is one of the oldest public art institutions in the United States. Unfortunately the work I have always valued within the museum are the very pieces the institution has so little regard for–I loved their Henri Matisse, Frida Kahlo, James Tissot, Monet, Manet and the other usual suspects of the impressionist movement–what I don’t give a rat’s ass about is their entire wing devoted to Clifford Still or any of the postmodern atrocities that populate the new building expansion.

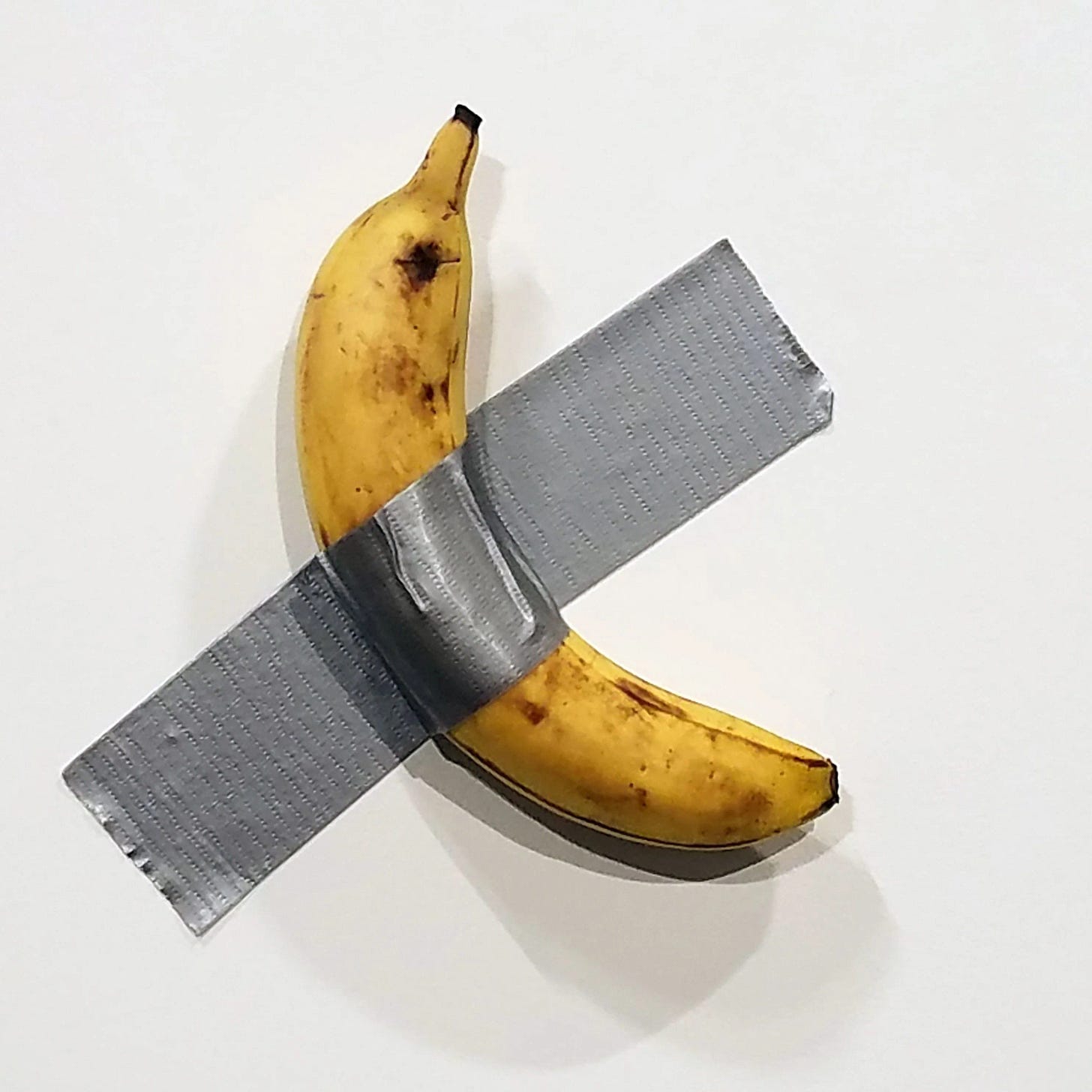

Spare me your 100,000-dollar banana duct taped to the wall, your million plus dollar Jeff Koons balloon dog, or your Damien Hirst shark encased in formaldehyde. I’m good. Admittedly the AKG does not have any of these items, but I am sure if they could purchase them they would. I was privy to their entire catalog while I was there–I know the initial cost of many of their postmodern purchases like the amount they paid for the work of Cindy Sherman–the artist I single-handedly blame for inventing “the selfie.”

It may seem like a strange segue to go from harping on AI to lamenting my hometown’s awful collection of postmodern travesties; but I assure you, I have an argument for how to link postmodernism to the machine learning generated editorial illustrations that look like they were done by an android wearing a MAGA hat.

Postmodern art comes from post-structural philosophy. Post-structuralism relies on the notion that there is no universal truth. Once again, we can all blame Foucault and his modern-day successor Judith Butler for ruining everything. If there is no universal truth, no “real” reality, then science can be anything you want it to be and therefore so can art. Feces on the sidewalk can be art, jumping up and down while screaming obscenities can be art, and so on and so forth. This kills valuing craft and makes way for grifters to come in and “subvert” normalcy or whatever.

Since we already had a fine art market built around irony and humoring the richest in our society with expensive curiosities dressed up as profound images it was natural for AI art to come in for the death knell of visual cultural consumption. When we value nonsense like paying 100,000 dollars for a Costco banana at Art Basal Miami (sorry second time I know–but it still boils my blood) what makes anyone think that at the lower end of the art market anyone would be willing to pay for anything drawn by hand? AI did not devalue art; we had already devalued it when we started putting literal toilet seats in museums.

Gender ideology and trans-humanism were both born out of the merging of technology and post structural philosophy–the destruction of the arts is an unfortunate casualty of this unholy alliance. It is interesting that a philosophical movement so concerned with destroying labels around identity would end up creating an entire mass movement based around them. Isn’t it funny that now, when technology is subsuming every facet of our lives, merging with us so we are both man and machine, we are more obsessed with identity than ever before? I wonder if it is a coincidence that as our individuality slips away, we cling even tighter to our identitarian politics and labels.

It would be hypocritical of me if I did not say that I resented AI and post-structuralism for destroying my identity as an artist. If you can simply identify your way into the art world by creating AI generated images–a phenomenon that is already underway, as AI art Instagram and Tik Tok accounts are already here; the value of what I do is depleted. It also makes me worried about where all of this is going.

When we kill creativity by outsourcing it to machines and we destroy truth by declaring that there is no truth, what do we value as a society? What cultural emblems will this era leave behind? Will there be anything tangible, compelling, and organically human left? These are probably questions left to future historians. But as an artist who makes stuff with my hands, I selfishly hope there is still a place for work like mine.

I do not believe in life after death—even if tech companies are working on ways to upload our brain waves to a giant computer in the sky. This is why visual markers of my existence on this planet are so important to me. It’s my way of signifying that I was here. It’s my legacy, that maybe someday, when I’m long gone, will end up in another human’s home. It’s my own unique portal-beyond death into my mind that doesn’t require a screen. While the rich may be fighting over ugly enormous Jeff Koons balloon dogs, and technological methods for immortality, I hope they don’t destroy my master plan of living forever through making art with a pen and pencil in hand.