Triggered. That’s the only word, the only feeling, the low hum in the background in my brain from this entire hellish week. When I use the word triggered I use it with intent. The curse words, the sarcasm, and the claims of having my PTSD symptoms heightened by events that happened from Saturday June 28th to today, Friday July 4th–are real, they are not a social construct, or a passing fashion statement.

I do not like the popularization of therapy-speak. Nor do I endorse or appreciate the gentrification of therapy culture and the normalization of terms like triggered. Being triggered isn’t a cute adjective to add after complaining to a friend about the trivial annoyances of modern life, or the banal reactions to the natural friction that happens with normal relationship hurdles; as psychologically compounded trauma literally does change how your brain functions on a neurological level. It is not a fad, a 30 second movie on TikTok, an Instagram Infographic, or a “sad girlie” fashion aesthetic.

Trauma is real neurological pain that changes how your nervous system operates and responds to environmentally induced stimuli. Trauma can shorten your lifespan, make you more likely to develop autoimmune disorders, heart disease, and hypertension–among other things. So, when I say that my nervous system has been over-reacting since 12 pm last Saturday the 28th of June, I mean it. I mean heightened flight or fight response, jumping at loud sounds, overreacting emotionally to benign emails and text messages–that’s what being triggered is.

This Saturday I attended my first ever dance class. I walked in cautiously optimistic and left knowing that at some point I was going to have to type out exactly what transpired in brutal detail. Five years ago, a date that now simultaneously feels so close and yet so far away from life now, I could never visualize myself rolling around on the floor of a hole in the wall dance studio in Philly, looking like a beached whale writhing in the sand, while a waifish instructor croons over a playlist of women artists that I assume mirror her in demeanor and temperament.

'“There are no rules.” she mummers.

My Saturday started out like all my other Saturdays in South Philly do. I woke up at the crack of 10:30 am feeling unaccomplished and exhausted, that’s what happens when you are keeping at least 20 constant tabs open in your brain for every uncompleted task you haven’t done yet–creative and otherwise. Once I grabbed my bearings and got my situational awareness back, I spent an inordinate amount of time catching up on world news before gradually making my way to my local cafe–or my usual weekend routine.

On this particular Saturday, I had to rush because this class was at noon, which is normally the hour of the day where I finally muster up the will to shower and become a whole human being again. So my reflexes and neuroticism were already elevated from not being able to do my normal thing of being extremely gross and lazy for 60 minutes.1

I have a beloved neighborhood cafe around the corner from where I live that truly lives up to the working definition of a proper urban third space. Everyone in the surrounding radius of Beth’s Cafe2 loves to kibitz and hang out there. People bring their dogs, their problems, trade in the latest neighborhood gossip, and come out with coffee. Beth’s is my tarmac for dealing with the rest of humanity, and my launch pad to casual interactions. Going to Beth’s is essentially a warm up exercise I do before having to put on my full social mask for the day.

My first mistake, kicking off a week of unfortunate personal and political events, was walking into Beth’s and unknowingly screwfaceing my dance instructor. At the time, I didn’t know that they were my dance instructor–I just saw the back of their Palestine Youth Movement t-shirt. But the graphics on the back were emotionally challenging enough for me to side-eye them as I entered the door on a mission to order a coffee.

I lingered at Beth’s for a bit, sitting at the counter chatting with a friend while the two women behind me glanced over while I talked really loudly about this dance class I was going to. Like the dumbass that I was, I was already digging my future social grave, cracking jokes about the title of the class–something to do with self-love.

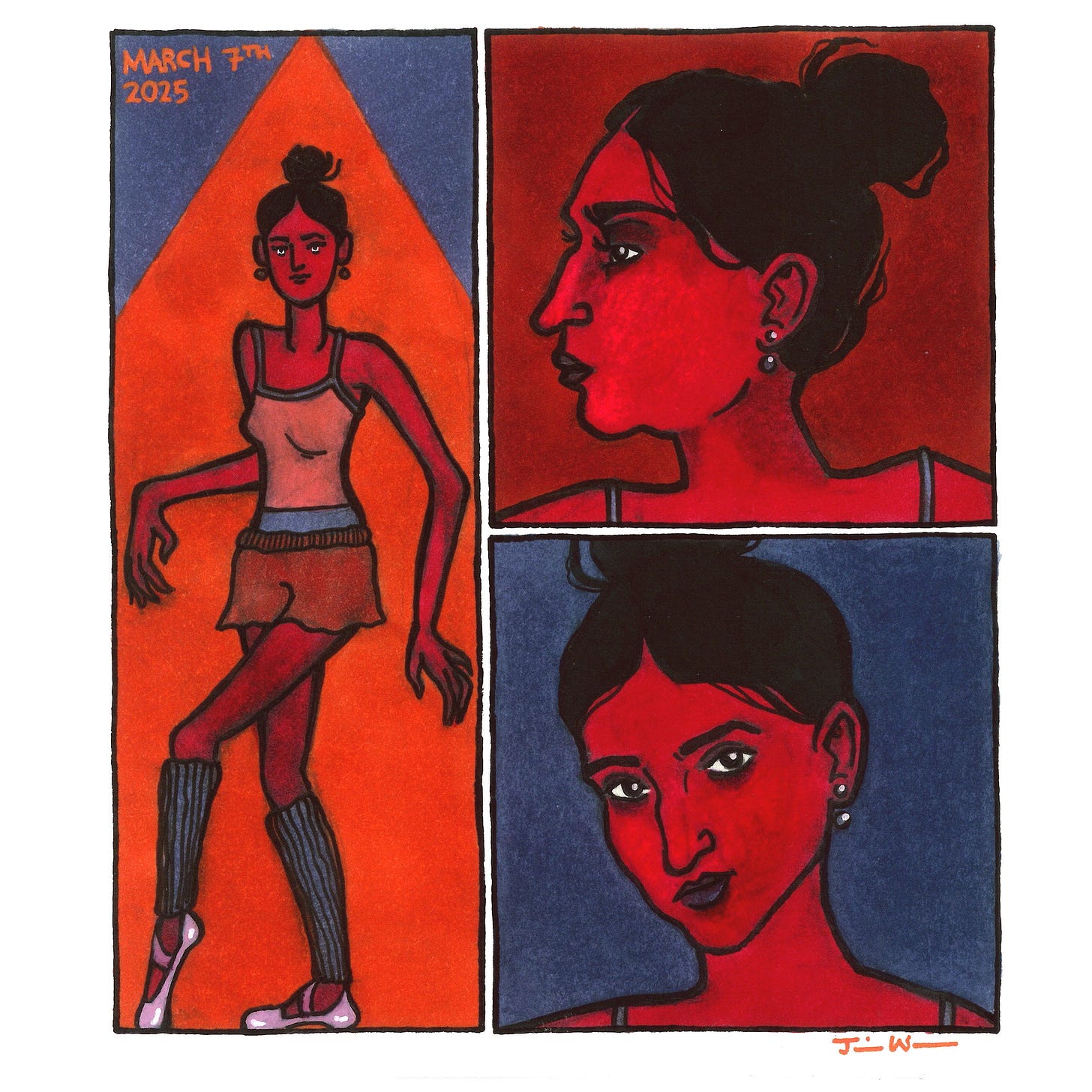

I had been ghosted by ballet classes. That’s the real reason I was attending this particular studio. I am working on a comic at the moment with a ballet studio in Los Angeles and I'm creatively stuck. It’s one of those open tabs in my head that keeps blinking because I can’t figure out a good plot line and I haven't gotten comfortable enough drawing dancers.

My current state of artistic block has driven me to start thinking about more immersive and experimental ways of gaining inspiration. That was the initial motive behind attending a class at Philly Dance Studio.3

“Go to Philly Dance Studio” I was told.

“The classes are cheap and they have courses for beginners.”

I left Beth’s a little nervous but excited about trying something new. Lately I have been doing a lot of new things: learning how to speak Spanish, learning how to read Arabic, taking boxing lessons, and I thought that dancing could be another new activity to fill some time with.

The dance studio building was at the bottom of a busy commercial strip in a neighborhood where the working class and middle class, the newly immigrated Salvadoreans, Hondurans, Mexicans, Cambodians, Vietnamese and Chinese, mingle with the older communities of Irish-Catholics, Italians, and Jews. I love it here. It feels like home.

But that feeling of togetherness dissipated for me when I entered the doors of Philly Dance Studio. That’s where I saw the front of my dance-instructor-to-be’s t-shirt.

She was a tiny woman, with light features, wearing a beige shirt that was three sizes too large for her delicate frame. There was a drawing of a man, his face shrouded in a keffiyeh, holding a machine gun–possibly a Kalashnikov but I cannot remember, with the phrase “resistance means radical love” beside him, taking up the rest of the garment’s negative space.

“Hey you’re the girl from the cafe!” A fellow student next to me on the floor said, looking in my direction. At this point, I was already entering fight-flight-fawn-freeze mode of my trauma disorder.

“Yes I am.” I said, my eyes averted, staring at the mirrors, the walls, the exit.

Have you ever disassociated? Have you ever been in a situation where you feel detached from your body? Because I am just grasping this irony now, of having a traumatic stress episode in an art class centered around love.

The other students started filtering in. They were all highly feminine looking women. Scrunchie wearing, Lululemon legging buying, Black Beauty reading, Barbie the movie watching kinds of women.

After all of us arrived, dressed in our athleisure and making awkward small talk, the class started. I was half debating walking out, but I had already taken off my shoes–which for normal people means putting them on again, and strutting out the door.

But for brain damaged people, figuring out how to gracefully exit a stressful social encounter means constructing a Rube Goldberg style thought contraption of conceptual levers and buttons, where, pulling the conversational springs and nobs determines what action you take. The thought logistics behind grabbing high top sneakers and having the time to lace them up while everyone else looked on stressed me out more than just swallowing my spit and joining the pronoun circle.

Some people were She/Her others were They/She, but no one was a He/Him. Then they got to me. “I don’t care, call me whatever you want…” blubbered out of my mouth, until I quickly course-corrected and mumbled “She/Her” like a good comrade.

The instructor adjusted her t-shirt, and gave us a small lecture about how important self-love is during a time of genocide. Which sounds almost like the title to a sequel of the Gabriel Garcia Marquez novel “Love in the Time of Cholera.” With the exception of the fact that my instructor was dead serious about the postmodern incantation that she was spouting, and the latter is a fictional story centered on two lovers living in late 1800s and early 1900s Colombia during a cholera outbreak.

After the red army prorabotka style struggle session, the dancing portion of the class commenced. Our Bambi-looking teacher put on music that I can only describe as what would happen to Michelle Branch, my favorite proto-Taylor Swift, early aughts folk/pop musician, if she married Philip Glass, a jazz composer that sounds like “Tinnitus the Band.”

Bambi, the bright-eyed, bushy tailed, Hamas t-shirt wearing, twig-like teacher, is now—at this point, telling us to artfully roll around on the floor. Encouraging us all to crawl and stretch our legs in the air. If viewed from above, I imagine we all looked like wiggling worms after a rainstorm in the middle of the sidewalk.

“You can do whatever you want to do,” Bambi crooned.

“You can go for a walk and come back.”

“You cannot listen to anything I say-or you can!”

“Up to you.”

And I thought about it. “If she says I can do whatever I want does that mean I can leave?” I pondered. I probably should have done that, I probably should have gotten up and excused myself to the bathroom and never looked back–but by this point I was in freeze mode.

I looked to my left and I looked to my right, everyone was hunched over swaying like tree branches on a blustery day, and I was the rigid light pole. I suddenly remembered what being back in my home city during the first decade of my adulthood was like–awkward, cold, hostile. That was the art scene I was brought up in, the obtusely pretentious and the performatively bad.

I lived in Untitled, the mid-2010s indie movie—but in real life. Where all the work is a smoke screen for force feeding you queer theory and solidarity. And everyone has read enough Butler and Zizek to pull thesis sized artist statements from their behinds to justify their lazy technique and underworked ideas.

I had forgotten how isolating that environment was, and how socially stressful it can be to be the other—the person who does not belong in a creative space but accidentally finds themselves there anyways. It is the closest feeling I think I will ever be able to get to experiencing a good old fashioned religious shunning. And the irony isn’t lost on me that those who think they are creating the most inclusive environments are the very people preaching hate.

For the rest of the class I tried to copy the other dancers, but none of them had moves I wanted to emulate. They were all dancing with the same energy and style of B-Girl Raygun, a professor of postmodern dance, and former 2024 Australian Olympic Break Dancing competitor.

Raygun became world famous at the 2024 games for her spastic, scattered, and ultimately ugly and untrained dance moves–so bad in fact, that they are considered by some people (that would be me) an affront to the entire genre. The students in my dance class appeared to be B-Girl Raygun proteges in their natural musical environment. Luckily for all of us–me included, that our dancing wasn’t done publicly. Because I also know that I cannot dance, hence why I wanted to take a dance class in the first place.

Honestly, the biggest crime out of all of this, is that now I’m afraid of dance classes, and I am afraid of going to art openings. I am afraid of going to concerts, and socializing for too long at bars. I am afraid of seeing symbols and having conversations that turn hostile because of who I am and what I think. It’s a pattern, it’s a system, and it’s something I have discussed with other Jewish artists. Our language, our identity, and our thoughts are being policed and politely shut out of the cultural space.

What I type is what I research and what I think. To make art as a person who does not go along with the new religious dogma is to be a political and spiritual heretic. Jews as a group, and Jews in the arts in particular, are learning this lesson once more now.

We are living in a world of postmodern Jew-Hatred, the kind that can be philosophized, excused, and morally relativised away. Antisemitism is a social construct, a state of mind, a performance. Thank you Foucault, thank you Butler, thank you Derrida. Truth is relative, so is hatred. If you ever wondered how postmodern and post-structuralist theory ruined art, I was living it, in real time.

We were instructed to ponder what love is, what truth is, how we “love” ourselves. But the only thing I could focus on was the t-shirt, the gun, the Orwellian slogan. This is what Newspeak looks like this is what Newspeak sounds like. Resistance is love, love is violence, violence is kindness–you get what I’m putting down, it’s 1984, its Brave New World, and its Fahrenheit 451.

And the slogans, the illustration of the masked gunman triggered another flashback. That’s the crazy thing about PTSD, is that you can time travel, but the visits are never to somewhere safe.

Suddenly I was back in Seattle, in the apartment building on 14th and Yesler, right above the offices of my District 3 city council representative, Kshama Sawant. Sawant, was the only socialist politician on a Seattle City Council that was already so blue in the face it was choking on its own insatiable need for new novel pronouns and power. Sawant represented the trendy arts district of Capitol Hill, the hospital dominated healthcare industry centric First Hill, the wealthy lush green enclaves overlooking Lake Washington and Mount Rainier of Madison Park, Madison Valley, and Leschi, and the rougher poorer neighborhood of the historically Black, Japanese, and Jewish Central District-which was where I lived.

When I lived in Seattle, I had New York State based friends who supported the DSA. I no longer do, but at the time they were my closest and oldest compatriots. I remember telling them stories about Sawant. About how most of her donations came from outside of our district. About how rabid and violent her supporters were. About how the “Recall Sawant Campaign” was started by a gay man of color, but was somehow spun around into being the work of a racist white supremacist who hated women.

I told them about how my neighborhood had deteriorated under her tenure and about how careless she was. I told them about how on the day of the brutal broad daylight murder of a small business owner in the Central District, a truly senseless violent act, ending the life of a young father and black business owner, Sawant had penned an open letter to SPD centered around her safety, in her plush upper class neighborhood. The murder of a young black father, who was providing an essential service to the community, an alternative to the post office, went unacknowledged by Sawant’s office for several days after the incident.

Just like Mamdani was not brought up by working class immigrants, Sawant’s whole political platform was based on half truths and deceitful slogans, on hypocritical campaign promises and unreachable-pie in the sky platitudes. With her persona protected by an army of Millennial and Gen-Z true believers, who punished dissenters and rewarded sycophants.

What was even more rich, is that Sawant has been routinely responsible for making her fellow city politicians unsafe. This was the same Sawant, who led protestors all the way to Mayor Jenny Durkan’s home, in the summer of 2020.

While I was never a Durkan fan, her address was protected because she was a former federal prosecutor. There is a federal law protecting the home addresses of lawyers and judges who work for the government because of the successful assassination of federal prosecutor Thomas Crane Wales in Seattle’s Queen Anne neighborhood in 2001.

None of my DSA-member Buffalo friends believed me. Sawant has been supported by Bernie Sanders in the past, much like Mamdani is being endorsed by Sanders now–and that was good enough for them. How can a politician be antisemitic if they have an “as a Jew” supporting them? how can a socialist hate Jews when Marx was a yid? The mystery continues.

I snap out of my hallucination and I catch sight of the shirt again, and I go from Sawant and draw a line to Mamdani. Mamdani and I are roughly the same age, which means we went to high school around the same time. I time travel again.

I think about Hutchinson Central Technical High School, which was the Bronx School of Science of Buffalo, the second largest city on the other side of the state from New York City. I think about how Mamdani and I went to similar schools, but about how the working class student population at Hutch Tech was very different from the wealth and privilege displayed at the Bronx School of Science.

I wonder what his experiences with refugee kids from former communist and Islamic countries is like. Did he know anyone who took their niqabh off when they came to school and put it back on before they went home for instance? Had he ever met kids who lived through the fracturing of Yugoslavia? Did he know any Iraqi girls who had to leave home to get away from their abusive fathers and the sexist demands of fundamentalist Islam? Did he ever talk to any Cambodian kids about spending the first several years of their lives in refugee camps, or know anyone whose parents fought on the wrong side in the Vietnam War and ended up in a re-education camp?

I do, I know these people, and I know their families. I have been to their houses deep on the east and west sides of the city.

I have worked on the factory floor with women from Laos, women from the Hmong and Miao ethnic groups. Women whose parents had fled the sectarian violence that broke out during the Vietnam War and the genocidal oppression of the invading communist armies. They would bring baskets of lotus cookies to work and share horrible stories about communist militias and sexual violence while simultaneously feeding you.

I wonder if Mamdani has ever worked in a factory, if he ever labored away in a building illuminated by neon lighting with no windows and slate grey concrete walls. If he ever did a job where he got his hands dirty. But I know the answer already. If he had these experiences he may not feel the same way about some of his policies.

I wondered if any of the women in my class had ever had to work on an assembly line, if any of them were forced to trade their dignity for a paycheck. If they knew what it was like to work at a place because you have to.

I thought about the neighborhood I lived in in Seattle and then I thought about what Zohran Mamdani had said about violence being a social construct:

I have come face to face with a person who has broken into my apartment building–it was traumatic. You feel vulnerable in a way that can only come over you when the threat of physical violence hangs in the air. Much like how my nervous system was now heightened by a diminutive woman dancing beside me in a t-shirt calling for violence against me and equating it with acts of love and righteous justice. Words are violence but violence is a construct. What I was feeling in that moment was a theory, a think piece.

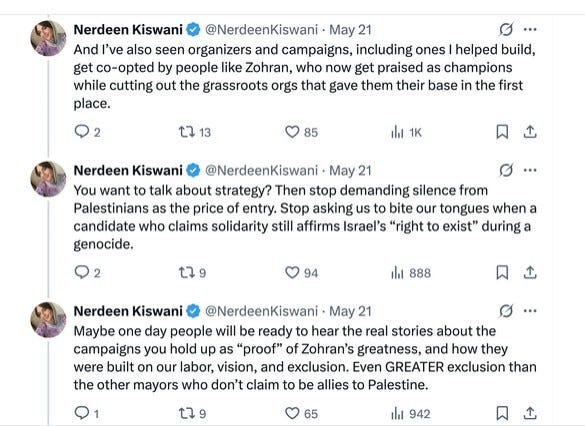

Just like the phrase “Globalize the Intifada” means “Resistance” or to “Shake Off.” A figure of speech Mamdani has used in the past as he is associated with the very person who popularized it–Within Our Lifetime’s (WOL) Nerdeen Kiswani. Kiswani is a woman who’s protest group WOL is directly affiliated with the PFLP, and an organization Mamdani himself has joined on pro-Palestinian marches.

Kiswani–was in fact peeved about Mamdani’s co-option of her patented “Globalize the Intifada” chant, and the distance he is now placing between himself and her organization while he runs for office.

Mamdani is the direct result of the contextualization of antisemitism. He is Jeremy Corbyn 2.0, an old doctrine in a younger body for a new audience. Intifada means resistance, Mein Kampf means my struggle, freedom is slavery.

There is no nuance, no veiled language, no post-structural philosophers to re-contextualize this phrase, because we no longer need them. We have dance instructors, baristas, and politicians who now moonlight as ideological enforcers for this neo-Maoist cult telling us proles how to think, how to feel, and what to say.

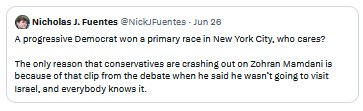

Sneako, a far-right manosphere streamer, voted for Mamdani to get back at Zionism. Sneako has been photographed at networking events and pro-Palestinian protests alongside David Duke, the former grand wizard of the KKK. Mamdani has also been defended by the likes of Nick Fuentes, a neo-Nazi whose famous for being Kanye West’s communications campaign manager during West’s brief run for president in 2020.

I wondered why no one was asking themselves why far right figures were endorsing politicians with far left policies. I wondered whether the women in my dance class thought about how they would be treated as people-with-vaginas in other parts of the world. Whether, we would be this free in Iran for instance; if we would be allowed to wear spandex outfits, and move to music. Whether we could opt out of restrictive gender roles let alone change genders all together in a place like Palestine. I know the answer—but my fear is that many of my peers do not.

My one hour from hell was thankfully coming to an end and I could feel freedom inching closer.

The worst part about not feeling safe in art spaces is that I still come away wanting the abuser, the bigot, the zealot to like me. Call it a chink in my emotional armor, but I always end up caring about my outward first impression more when it’s someone I know is against nearly everything I believe in. I think it’s because of how political disagreements have started to mimic moral codes.

Now, our political rivals aren’t only wrong, they are evil. Our arguments aren’t only temporary moments of discomfort but spiritual battles. Politics has become our hobby, and our subculture; filling the god-shaped hole where we once nurtured our psyches with art.

I have lived many different lives, and I used to know the kinds of people I was in class with. I used to try to make them my friends. I used to know what kind of art they made and attended their performances, workshops, gallery openings, and shows. The art was always hollow. A husk of a creative project blanketed in postmodernist thought to give the viewer the false sense of artistic nourishment.

None of us were the next Picasso. And how could we be, when the most famous artist in the world in our current era is Banksy—an individual who makes work that visually embodies the age of managerial class socialism. In an era where AI image creation is now the norm, destroying the jobs of countless visual artists, designers, and illustrators, how can we have great art?

It’s hard to aspire to be a Tomi Ungerer in a world of artificially created Mr. Brainwashes attempting to become the next digital Andy Warhol.

Dance class was finally nearing its end and I could see the light of the door in the studio getting brighter. I stared at my shoes longingly wishing to have them back on my feet again. As I knew I was infiltrating a space that wasn’t made for me, but for a hostile community guarded by social tests and coded language that was meant to bar people like me from returning. I tried to be polite, and to not make a hasty exist. I tried to put my shoes on like I was taking my time and not mentally spiraling.

“I like your shirt!” a tall girl in basketball shorts exclaimed.

That was my warning–time to book it out of there.

This was my second encounter in less than a month’s time with overt antisemitism. The t-shirt was not a dog-whistle but a bullhorn. Announcing rudely and loudly where my instructor ideologically stood. And she stood like many people in the creative classes on the same side as Sneako, David Duke, and Nick Fuentes.

Horseshoe Theory is now Oval Theory. When you have neo-Nazis who have endorsed Trump in the past supporting a far left political candidate, that’s when you ask yourself what side of history are you really on? The Jews aren’t on trial here–you are.

I sat for a very long time, deep into the evening watching the sky change from gold to orange to purple to navy, piecing together in my mind what just happened. Was it real? Am I over-reacting? Am I just being sensitive? I still don’t know.

What I do know, is that no one knows enough to hate each other this much. No one knows enough to wear t-shirts with violent imagery or to chant genocidal slogans.

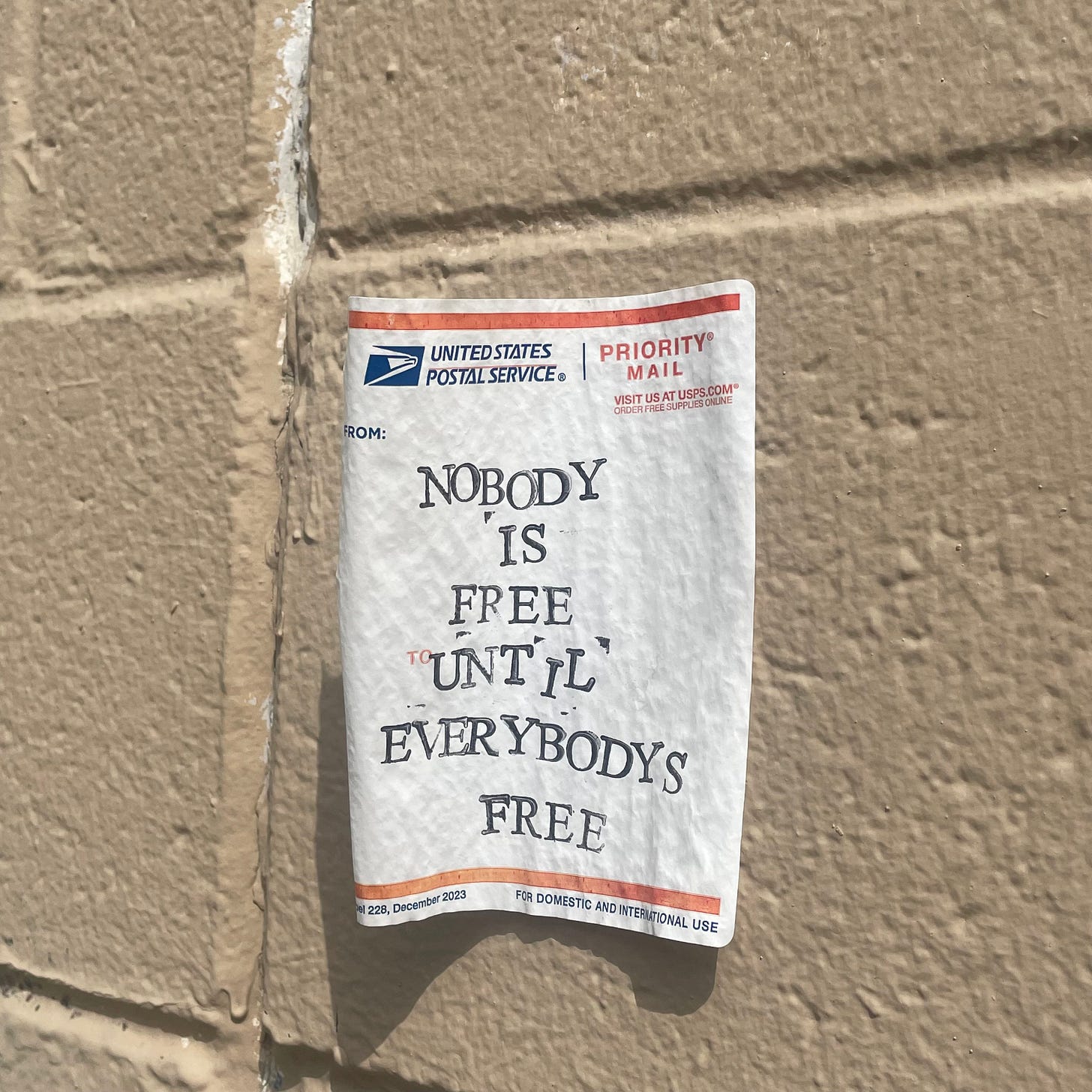

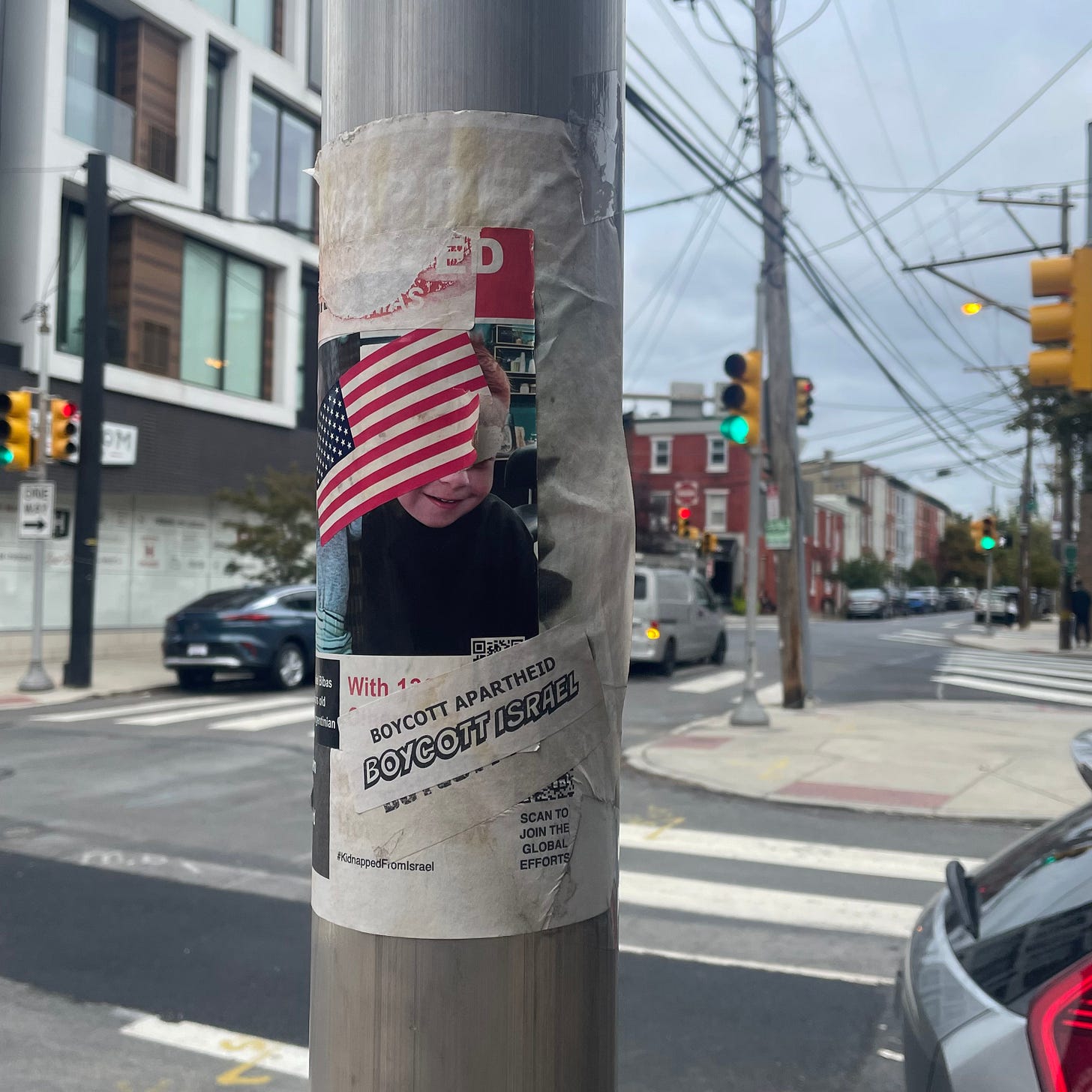

We are your neighbors, we see your graffiti and we read your antifa stickers. I am your neighbor, I am attending your dance classes, and buying coffee at the same cafe as you. Wasn’t it Shylock, the money lender in the Merchant of Venice that asked the gentile if the Jew also bled the same blood? Felt the same pain? Feared the same things?

Are we human or projections? Why must our fear and anxiety always be followed by a caveat, a citation? An if, a but, a question about how we feel about Gaza? An asterisk? Why must we be expected to end our essays, text messages, phone calls, with a song and dance routine where we wring our hands and apologize for our existence, our opinions, our humanity?

On the same day as my dance class from Dante’s fifth circle of hell, a band named Bob Vylan went on stage at Glastonbury and shouted “Death Death to the IDF!” Their performance was broadcasted live via the BBC while millions of people at home in the United Kingdom watched as an ecstatic audience repeated a chant in unison to annihilate a country and a people.

I know people personally who have served in the IDF. They have young children, they are scientists, they are musicians, they are artists. They are people like you and me.

I won’t linger on the quality of Vylan’s music—I did listen to it, but none of it is very good. It’s angry without being righteous and dumb without being funny. It’s what I would consider slop. Slop is music that masquerades as art but in reality is political propaganda. It is faux-edginess marketed as art to the masses by our corporate overlords. It is not subversive, it is not sonically interesting, it is not artistically satiating.

Which makes me wonder where all the fun, the beautiful, interesting art has gone. Why are we living in an era of uninspired work, created by people whose sole goal appears to be becoming famous, and whose sole purpose appears to be loving themselves at the expense of hurting large groups of other people?

Everything now is self-care, even calling for mass murder. It’s all about comfort, surface level empathy, performance art, and living as your superficially manufactured authentic self.

Bob Vylan named their band after a Jew. Their fame came at the expense of Jewish pain, and their namesake is riding on the coattails of a much more famous and much more talented Jewish musician. A Jew who wrote songs that will be remembered long after Vyan’s 15 seconds of internet outrage fame is over. Songs like Neighborhood Bully. A song about Israel. A song about global antisemitism and double standards. A song about a people who are always on trial, and always told by outsiders how they should feel. A song about living in a bad neighborhood among hostile cohabitants.

This week, Karen Diamond succumbed to her burn wounds from the bigoted attack on Jewish seniors in Boulder, Colorado. Her murderer is already being immortalized on Muslim Brotherhood affiliated Telegram channels alongside DC terror perpetrator Elias Rodriguez. An old Jewish woman is dead because violence is a social construct and Intifada means resistance.

I knew a person who witnessed the attack. Someone real who was there, holding a flag, participating in the rally. She is physically ok, but I cannot imagine what she is going through emotionally.

I have been to affiliated events in Philly, where the group is encompassed almost entirely by elderly Jews, and the demonstration ends with the crowd singing Hatikvah followed by the American National Anthem. Butler, Kiswani, Mamdani, the women in my dance class, would probably call this gathering of geriatric Jews a far right hate rally.

I spent the rest of the week in a state of dissociation. I missed mother’s day, I dragged my feet at work, I wondered whether my ex-friends thought about me at all. Whether they cared that my life and my friends’ lives could be at risk just by attending a demonstration where the Star of David was present. Or whether they would justify away murderous hatred against us too.

I got invited to show art at a major music festival in the Pacific Northwest at the end of summer. The organizers want me to show art with a group called “Vanishing Seattle,” which is a popular website and social media account that documents the ebbs and flows of Seattle neighborhoods through art and found objects. They want to take three of my pieces of old Central District and Pioneer Square architecture for the gallery event that runs in conjunction with the music acts.

After this weekend, after Glastonbury, after dancing with femmes for fatalism, after marinating in this environment for 20 months, I am no longer sure I want to visit my old stomping grounds, my old neighborhood.

Because resistance is love, love is martyrdom, and us Jews are just over-reacting.

No one is not disgusting, I’m sorry–apes are not pretty animals. Seahorses, tropical birds, orchids? you can list so many prettier organisms. Have you ever looked at pictures of protozoa!? Just saying we’re weird looking creatures. This is why I’m an agnostic because there is no way we are the ideal image of god–if there is a god or god(s). Tardigrades–now that’s the winner.

Not the real name.

Not the real name